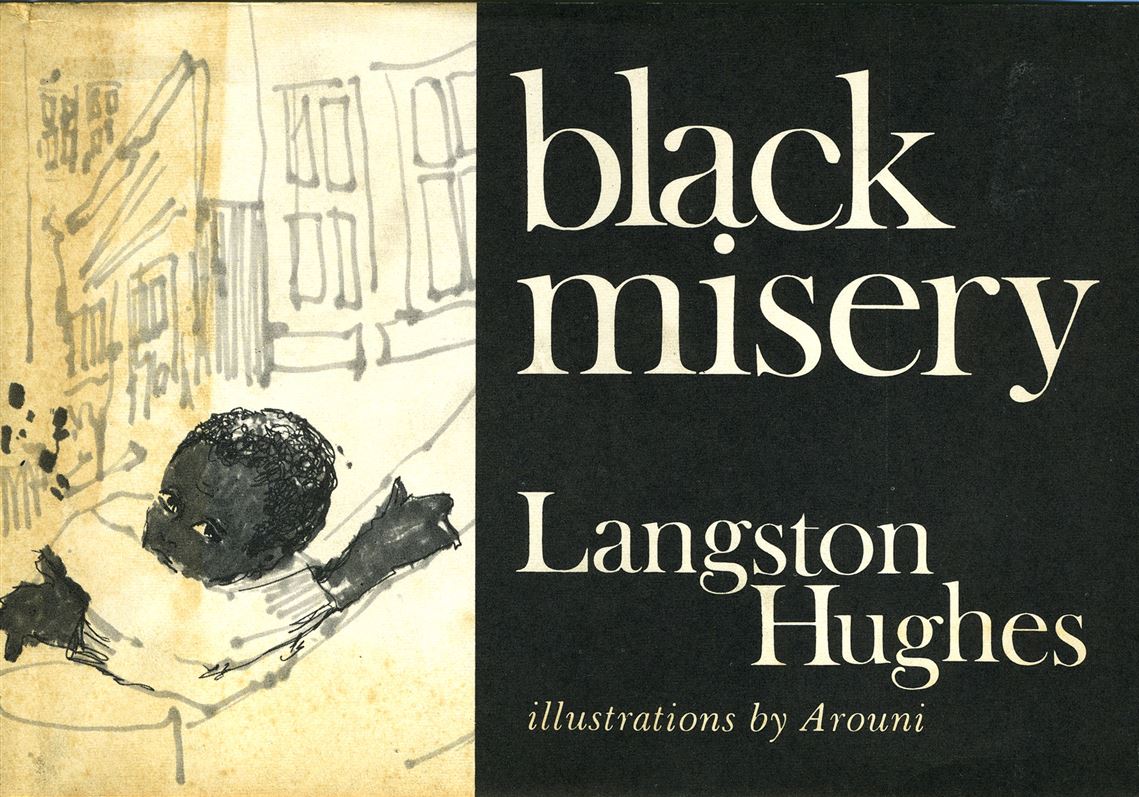

That stark moment when a child sees that the world is always going to be different for them than it is for others in their world. It's a moment when a Black child begins to recognize white privilege. In those cruel moments, children understand: the world is telling you that you'd better start learning the limitations of your place in it. In Black Misery, Langston Hughes captured such moments with a hefty emotional punch using very few words on each page.

"Misery is when you find out your bosom buddy can go in the swimming pool but you can't." An illustration shows a child standing outside the pool fence, looking dispiritedly at a pool full of white children playing in the water. Each page illustrates a different such moment in the experience of a child.

This was the last book Hughes wrote not long before his death in 1967. In an introduction, the Reverend Jesse Jackson wrote a few of his own childhood moments of misery in the context of race-coded times. Some of the circumstances described in this book have since been outlawed. Public swimming pools are no longer exclusive, public education and public transportation no longer segregated. Yet we can't satisfy ourselves with a belief that discrimination and its attendant pain and discouragement no longer exist simply because laws have changed. The stubborn economic and social realities of American life ensure that moments like these are still experienced by minority children in the US. The ugliness remains; only the contexts have changed.

A few years ago, a brainy, unfailingly polite, open-hearted and academically excellent 6-year-old I worked with in a tutoring center confided sadly to me one day that "the white girls" at his school had told him he couldn't play with them because he was "mean." This was a ridiculously inaccurate description of him, and this big-hearted child was baffled very painfully by this social slight. Stark moments like this in children's lives undoubtedly happen all around us, largely unnoticed except to those on the receiving end of such careless cruelty. It's a different version of the Black misery than what Hughes and Jackson and their respective generations experienced, but no less real and perhaps no less frequent.

This short, beautifully illustrated gem of a book delivers a powerful emotional impact, enabling us to see things we ordinarily don't about the spirit-diminishing effects of the racism that still permeates American life.

-Marianne W.

No comments:

Post a Comment